Last year, before he passed away, Ratan Tata made headlines for ensuring all street dogs got ‘free entry’ at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Colaba. In Tamil Nadu, former chief minister M. Karunanidhi was a dog lover, and for many years, his regular walk at party headquarters, Anna Arivalayam, wouldn’t be complete without the street dog there accompanying him.

The more you look, the more you’ll see love for streeties across the country. People spend lakhs of their own money to treat the dog down their street who has a tumour; women take the onus of feeding fresh food to 200 dogs across a city; others quarrel with their families to take in an injured dog — stories like these are increasingly common.

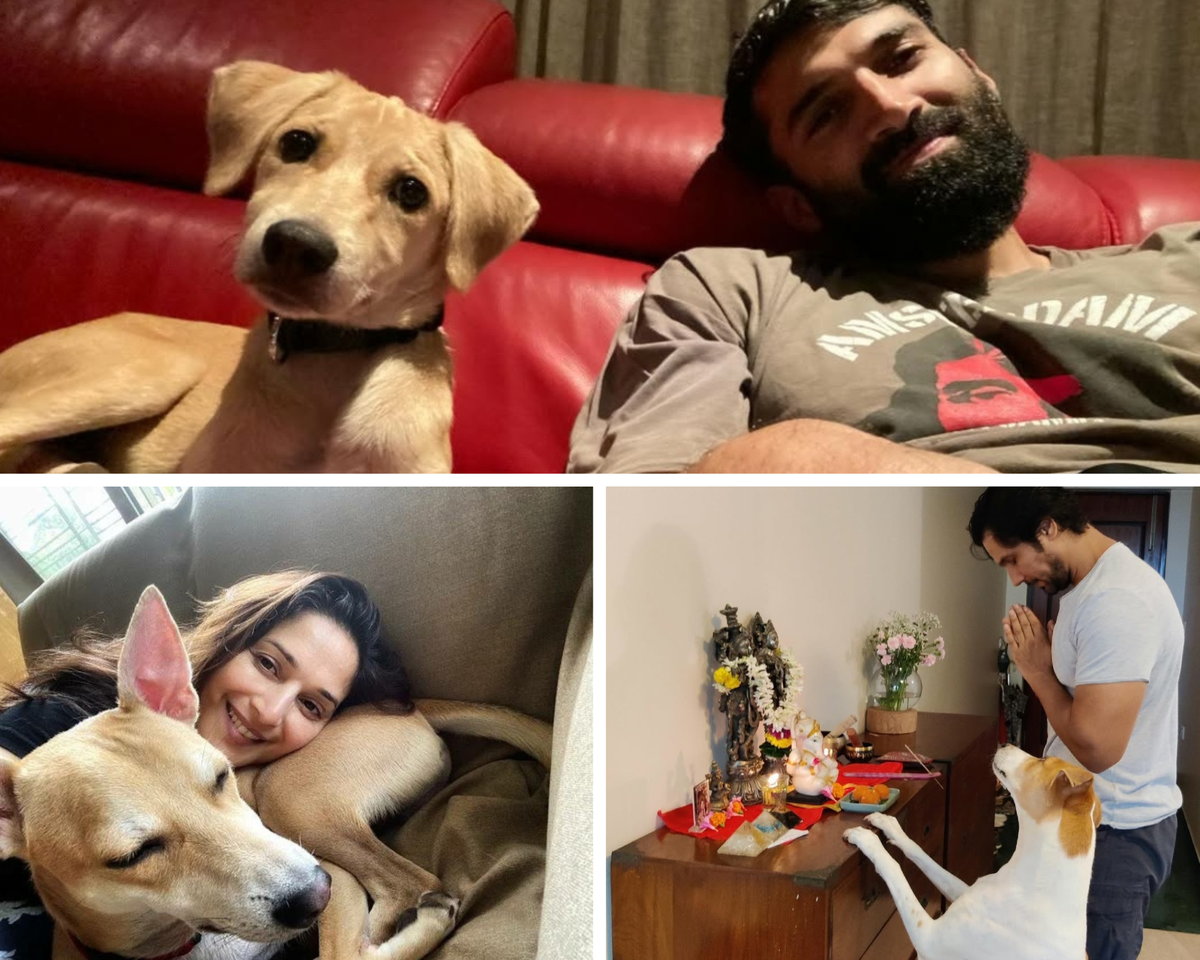

Celebrities often make headlines for adopting street dogs. (Clockwise from top) Aditya Roy Kapoor with his rescue, and Randeep Hooda and Madhuri Dixit with their dogs.

But so are the stories of legions of gated societies, resident welfare associations (RWAs) and market associations at perpetual war with the dogs in their area, to the extent that they pay catchers to, at best, drop off neighbourhood dogs in nearby forests and, at worst, dispose of them. Their reasons are also unassailable: if a dog is biting passersby, maybe even children, what is to be done?

The issue is fraught and tends to ignite high passions on either side. So, what is the solution to the street dog issue and more importantly, which cities are getting it right? “In every city, there is a very small minority that says, remove the dogs. There’s an equally small pro-animal lobby. And then we have the silent majority of 85%, who just keep quiet,” says Chinny Krishna, founder of Blue Cross of India.

Chinny Krishna

Since Independence, India has dealt with street dogs the only way it knew how: catch and kill. Dogs were shot, poisoned with strychnine, clubbed, drowned and electrocuted by municipal corporations across the country. The killing went up from a few dogs in the 1910s to more than 16,000 in the 1960s. In spite of this, the number of dogs showed no sign of reducing, and rabies deaths kept increasing. The reason was simple: existing dogs kept breeding twice a year. As one activist emphasised, a single unsterilised female dog and her offspring can potentially lead to the birth of 67,000 dogs in six years. That’s when corporations, spurred by animal rights NGOs, decided to try something different.

Chennai, in collaboration with the Blue Cross of India, was one of the first cities to experiment with the Animal Birth Control (ABC) programme in 1996. “We called it ABC to show authorities that control of the street dog population was as simple as ABC,” recalls Krishna. Mumbai began soon after, and within a few years, the programme had spread to a number of cities. It got its final seal of approval in 2001, when the Indian government, under the guidance of the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI), formalised the ABC (Dogs) Rules under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960.

Jeyaram, a waste picker, with his pet dog Benny in Chennai

| Photo Credit:

Akhila Easwaran

Things have gone astray

Cut to the present, and the implementation of the programme has been varied. Though some cities have fared better than others, a few consistent problems have been plaguing them all.

For starters, most corporation-run ABC centres do sterilisations on a complaint-basis rather than area-basis. So, if they get a complaint from residents of, say, Chennai’s Alwarpet, they’ll catch dogs in that one lane. Instead, they should be conducting area-wise sweeps, i.e., rounding up all the dogs in an area, sterilising them, before moving on to the next area.

Exacerbating matters is the poor to downright horrific quality of care in many of these government centres. Stories of botched-up surgeries performed by junior staffers and assistants, sometimes without anaesthesia, and with little post-operative care, are now so common that when feeders hear their dog has been picked up by the corporation, they’re terrified. “If only we had done everything in a proper, scientific, systematic manner, without any corruption, we would not be in the mess that we are in today,” says Shravan Krishnan, who runs Besant Memorial Animal Dispensary in Chennai.

“One of the issues with the vet system in India is that often the people who opt for veterinary science appear to be those who have not succeeded in their MBBS ambitions. So we’ve got vets who are not really interested in animal welfare, who are mostly holding out for a government job. So, obviously, the quality of vet care is not the best.”Kiran RaoChennai-based entrepreneur and animal activist

Kiran Rao

The city, a pioneer of the ABC programme, is not doing too well in its implementation, according to several vets, NGOs and local Animal Welfare Board members. It has five ABC centres run by the corporation. In addition, it partners with NGOs by offering them infrastructure and monetary help to perform sterilisations. Krishnan had the chance to tie-up with the corporation. Theoretically, this would have afforded him the use of corporation-hired dog catchers and a sum of anywhere between ₹500 and ₹1,500 per surgery. “But I didn’t want to do it,” he says point blank.

For starters, according to Krishnan, there is a lot of corruption in the system. Instead of getting money, he says, he’d have had to pay at least ₹100 per surgery as a bribe to officials who come for inspections. Any money he got after that would be delayed for months. On top of it, he was unsure of the quality of corporation dog-catchers.“They usually catch them in a cruel way, and post-surgery, might drop them off in a different area from where they were picked up,” says Krishnan. Instead, he has opted for a community-based system, where people who feed street dogs in the area bring them to him for sterilisation. This way, he manages to do around 3,000 sterilisations a year, all without having to catch a single dog.

According to a recent survey conducted by the Chennai Corporation in partnership with the World Veterinary Services (WVS), the city currently has a street dog population of 1.8 lakhs, a significant jump from 57,366 in 2021. Of these, the survey estimates, almost 73% are unsterilised. “But now that we have exact data, we know precisely which zones to target,” says Antony Rubin, who is part of the city’s ABC Monitoring Committee.

The city-wide stray dog census

| Photo Credit:

B. Jothi Ramalingam

Tamil Nadu also recently managed to secure an additional ₹20 crore of funding to expedite ABC — which will go towards grants for existing NGOs as well as opening new ABC centres. They’re also planning on opening a training centre where veterinarians across corporations and SPCAs (Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) will be trained in the correct way to perform ABC surgeries.

“The tragic incident of an 18-month toddler being mauled to death by street dogs last year led to heightened anti-street dog sentiment in Hyderabad, with increased public concern over dog attacks. In reality, this is an issue across India, with cities that are ever extending, and the growing garbage waste to deal with. Dogs often thrive on this garbage. City suburbs and outskirts need dog management programmes. Instead of reactive services after dog bites take place, it calls for proactive services.”Amala Akkineni Blue Cross Hyderabad

Amala Akkineni

Bigger cities, more resources

Usually, bigger cities have an abundance of people and resources, which translates into street dogs that are better fed and cared for. “Larger cities generally do a better job, because at least people are feeding the animals,” says Anjali Gopalan of the AWBI. Delhi currently runs a whopping 21 ABC centres across the city and its outskirts in collaboration with NGOs. With the partnership model, the city provides the space, dog-catching resources, and monetary help of ₹1,450 per surgery. The rest falls on the NGOs.

But according to Ambika Shukla of People for Animals (PFA), which has tied up with the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) to run the Sanjay Gandhi Animal Care Centre, quality varies from centre to centre. At the PFA centre, for instance, dogs are brought to them by the MCD. “The first thing we do is tag the dogs. Each tag has a number, with an address, the date the dog was brought in, its condition, description and a photo,” says Shukla. If the dog looks weak, a blood test is done to ensure he/she is fit for surgery. This is followed by the operation and post-op care of at least five days. Then the MCD drops off the dog in the same area it was picked up from. “Normally we are in touch with the feeders to ensure the dog has reached back safely.”

Ambika Shukla

But not all NGOs are so scrupulous and Shukla highlights how some corporation-funded centres are running on no infrastructure and unqualified staff, leading to shoddy surgeries. “It’s basically a single doctor operation,” says Shukla, a practice which is illegal under the latest iteration of the ABC Rules, 2023. Moreover, there is very little oversight on the part of the MCD — there is no ABC Monitoring Committee, which is supposed to review progress of the sterilisation program and put out statistics, and the Veterinary Services Department at the MCD has had no director since 2023. “There’s an overall lack of accountability,” says Shukla.

Noida too, with its many affluent housing societies, has its fair share of animal lovers. Pallavi Dar, a resident of Sector 17, feeds and cares for 200 dogs every day across Sector 18, 19, Film City, Rajnigandha Chowk and BHEL Towneship. Feeders like her often ignite the hatred of people, who think they are exacerbating the dog problem. “Feeders are usually women, mostly young or older single women, and RWAs in these colonies are extremely violent towards them, sometimes even resorting to physical violence. They also make up stories and frame them,” says Gopalan.

In actuality, it is people like Dar — who feed the dogs every day and have a relationship with them — who help catch and sterilise them. “Just think about it: why would I want an unsterilised dog roaming around in my area? Tomorrow she will give birth to puppies and I will go from feeding 200 to 207 dogs,” says Dar.

Pallavi Dar

The other side

According to Amit Sarin, general secretary of the Qutub Plaza Market Association in Gurugram, their market in Phase 1 has been facing a street dog issue for a while now. The last couple of years have seen incidents of dogs biting shoppers, even children; increasing food and garbage piling up; and an overall hit to businesses as people are too scared to shop there. The reason, says Sarin, are three women who live nearby and feed and care for the dogs. “I’m a dog lover too, but having these dogs here is just not practical. This is our place of work, and beyond a point, businesses are suffering and people are scared,” he says, adding that he has tried many times to initiate talks with the feeders, so they could come up with a solution together. Perhaps they could create sheds for the dogs in a corner of the market. “But they refuse to come to the table, and whenever I try talking to them, they make me feel like I’m a dog hater,” he adds. They even filed a harassment case against Sarin with the AWBI. In its aftermath, he has given up — and the street dog issue at the market persists.

Many are struggling

Unsurprisingly, smaller towns and cities have it much worse. Rubin of Chennai’s ABC Monitoring Committee divulges how, many times, smaller towns, under pressure from people and societies, pick up dogs from cities and drop them off near villages and forest areas. “This is very dangerous, since dogs can spread diseases to wild animals. There were cases of a jackal and a leopard cub getting infected with canine distemper and rabies,” he says.

In Goa, while the cities are taking some steps, in the interiors, sterilisations aren’t being done, says Atul Sarin, of the NGO Welfare for Animals in Goa. “We need a lot more NGOs if we’re going to succeed, especially in the panchayats and suburbs.” The influx of tourists has also presented a unique problem: the summer and winter months see a rampant breeding of street dogs due to leftover food and bad garbage management, and come monsoon, the same dogs starve to death due to scarcity of food. As of date, only eight of 14 urban local bodies and 43 of 191 panchayats in the state are conducting sterilisations.

A woman pets a street dog at an adoption drive in Kochi

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

In Kerala, Kochi is the only city with a corporation-run ABC programme. And while they have sterilised around 8,000 dogs in the last seven years, the process has been quite haphazard. For instance, the centre was closed for a few months for renovation, and reopened only last July. “Moreover, the centre doesn’t have many of the facilities that the AWBI has mandated [hygiene, equipment, CCTV cameras, prescribed cages],” says T.K. Sajeev, secretary of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). “The reason why we haven’t complained is because if it shuts, then there is no one else.”

A few NGOs such as Daya Foundation and Animal Rescue Kochi are doing a limited number of sterilisations with their own funds — as long as someone brings the dog to them and takes it back home for post-operative care. “But many of these NGOs are in debt, and don’t even have money to pay their vets,” says Tanja Fernandes, a dog-lover who has rescued multiple dogs over the years.

Tanja Fernandes

In many cases, animal lovers are ready to pay for someone to catch dogs in their area and sterilise them, but with no organisation, government or private, supporting it, things are tough. The consequence is that street dogs, many of them unsterilised and unvaccinated, are wreaking havoc in the city. Recently, students at the Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT) went on strike against the “stray dog menace” on campus. Last October, four dogs were found dead on campus — one died from rabies and the other three were suspected to be poisoned. “The authorities have started killing the dogs there,” laments Fernandes.

In Kolkata, the city has a single corporation-run dog pound that does ABC on the side. But, it does not permit visitors and this has eroded trust among the dog-loving community, who believe this is because of botched-up surgeries and mistreatment of animals. Consequently, feeders and rescuers across the city choose to take their street dogs to private facilities, often paying money out of their own pockets to get them sterilised and vaccinated.

Chhaya Animal Welfare Hospital and Rescue Shelter is one such facility on the outskirts of the city. “We get calls about all kinds of things — injured animals on the road, abuse cases, vaccination, sterilisation,” says Sharda Radhakrishnan, the founder. In each case, their van goes out to pick up the animal and brings it to Chhaya’s huge 200-acre premises. “The people calling us are mostly small shopkeepers, maids, rickshaw drivers, students. There’s no way we can charge them because they’re not going to be able to afford it. So, we provide service free of cost, and try and raise donations.”

Sharda Radhakrishnan

Stricter licensing requirements

The law around street dogs in India has been consistently evolving. When the government stopped mass culling in the 90s, it passed the ABC (Dogs) Rules, 2001 that mandated corporations across the country to sterilise, not kill, street dogs. The rules were recently updated, culminating in the ABC Rules, 2023. Some of the most significant changes include banning relocation of street dogs from one area to another; mandating all NGOs conducting sterilisations to be registered with the AWBI; and overall, emphasising a more humane treatment of animals throughout the process.

Anjali Gopalan of AWBI

But there’s still a long way to go when it comes to their implementation. “For any law to be implemented, there has to be a strong acceptance from society,” says Vikram Chandravanshi, legal advisor at AWBI. “What we’re currently lacking is societal acceptance.”

The new ABC rules also have a flip side: they have made it much harder for NGOs to get permission for sterilisations. “A lot of the requirements are unrealistic and difficult to fulfil. NGOs are struggling to begin with, so making it harder for them won’t be productive,” says Goa’s Sarin, whose NGO filled the AWBI-mandated paperwork in 2023, and heard back almost a year later. This complaint was repeated by a number of NGOs in different cities.

In response, AWBI’s Gopalan stresses that it is not difficult to get these permissions if all the documents are in place. “We have a committee which reviews everything. Many times, they [applicants] don’t fill it out properly, and we have to tell them to re-submit or ask for clarifications. And that process does take time,” she says, adding that there have also been instances of NGOs misusing government funds and mistreating animals. “So we have to be careful.”

Suggestions for corporations

Ensure veterinary hospitals in the city, under the supervision of the veterinary officer, do a base minimum of sterilisations a month

Have CCTV cameras in all ABC centres (in the operation theatre and post-op cages) and make visiting hours mandatory

Encourage each RWA to appoint an animal welfare group

Carry out a systematic public education campaign to make people aware of laws around street dogs. For example, Bengaluru has started using its garbage collection vans to broadcast information around animal welfare laws and dos/don’ts

Model cities

At the moment, two cities are leading the way when it comes to streeties. The biggest reason: a strong, symbiotic relationship between dog lovers and NGOs, and local government authorities. Bengaluru and Mumbai have an extremely proactive and practical animal welfare community that recognises the importance of working with the government.

Bengaluru has an ABC centre in each of its eight zones, and each is required to do 400 surgeries a month, for which they get paid anywhere between ₹1,200 and ₹1,500 per surgery. But that’s not all. The city’s dog lovers have developed a unique hub-and-spoke model to keep the ABC centres accountable, says activist Priya Chetty Rajagopal. There’s a city-wide Facebook group, where people can post concerns about the dogs in their area, and under this are around 55 WhatsApp groups called ‘Dog Squads’ for different areas of the city. These squads include not just dog lovers, but also representatives from the local ABC centre, private veterinarians, and RWA members. It’s a decentralised system that boosts accountability.

Priya Chetty Rajagopal

Rajagopal also stresses the importance of giving every community dog names. In the Cubbon Park vicinity, where she lives, every dog has a collar with a QR code that, once scanned, gives you the backstory of the dog, including its name, age, and quintessential traits. “There’s Rock Hudson, Madame Butterfly, Poppins, Buddy Boy, Scrappy Doo, Mad Butterfly. We have the entire BSNL gang 3G, 4G, 5G, Jingle, Ringtone,” she laughs. “So, it’s not just a brown dog in the corner, it’s Jingle. The moment you give them an identity, people don’t mess with them.” According to Rajagopal’s estimate, approximately 60% of Bengaluru’s dogs are currently sterilised and vaccinated.

The situation is even better in Mumbai, where the dog sterilisation programme has been so successful that a lot of NGOs have shifted focus to cats. “Because the moment the dog population starts going down, cats shoot up,” says Abodh Aras, CEO of Welfare of Street Dogs (WSD), an NGO which works with the local government to sterilise street dogs.

Aras’ is one of three NGOs working with the government. WSD decided a long time back to not accept any money from the corporation as there was a lot of corruption; instead they pay their 40 employees via donations. They are responsible for covering the entire island city, i.e., everything from Colaba in the south to Sion in the north — and they have done such a good job that according to their estimates, 80% of street dogs on the island are sterilised.

Their success, Aras says, can be attributed to three things: one, they did systematic area-wise coverage, ensuring they sterilised at least 90% of the dogs. Two, it was a continuous effort. “You can’t sterilise a large number of dogs in a year or two and then do nothing later. You have to keep at it.” And three, they constantly collaborated with feeders and caregivers in the community. “We started on-site first aid programmes, where we went into communities like Dharavi and started treating dogs and cats for maggot wounds, skin problems and so on,” he says. This helped build trust, which led to the chai-wallahs, ricksha-wallahs and didis feeding dogs in that community to bring their dogs to WSD for sterilisation.

Apart from this, the ABC program falls under the city’s veterinary department, which is quite proactive and responsive to NGOs needs. “We still get calls from the interiors like Kamathipura and Mohammed Ali Road, even suburban areas like Ulhasnagar, Dombivali, and Virar,” says Kanan Shah, who runs an animal ambulance service under her NGO, The Zara Animal Project, which funds and ferries dogs and cats to the nearest shelter/ABC centre for sterilisation. A cursory look at their Instagram page reveals a model of transparency: they regularly upload pictures of every dog they pick up, coupled with details of place and date. “Everyone’s out there, pooling their resources and doing what they can,” says Shah.

Kanan Shah

It’s obvious that there’s a long way to go before India can achieve 100% sterilisation and meet the goal of a rabies-free country. What we need is cities talking to each other and sharing best practices. The rest will follow.

The writer is based in New Delhi.

Published – January 17, 2025 06:45 pm IST

#Fixing #Indias #street #dog #problem #simple #ABC