Grey skies loom, merging in the horizon with the neon green that surrounds us in Goa during the monsoon. We are drenched and cold on a small wooden boat with a very loud engine, gliding through the inner rivers of North Goa. I have come netfishing with Tukaram Chodankar, a professional fisherman who has been fishing since he was three. There is a moment of silence before both his net and the rain are unleashed together.

I can barely see through the rain, while Chodankar deftly brings the net in, splashing mudoshi (lady fish), chonak (giant sea perch) and tamoshi (red snapper) into the bucket next to my feet. Rain or shine, he is out on the Moira river every day catching fish that he sells in the market. The size of his net determines his catch, its wider weave ensuring he only catches the larger fish, letting babies and any shellfish through. “As a fisherman, it is my duty to make sure I leave behind enough in the river for my own future,” he says.

On the river with Tukaram Chodankar

| Photo Credit:

Simrit Malhi

Nitesh Shetkar, a young taxi driver and Chodankar’s friend, also regularly goes fishing “because it’s what my father used to do, and his father before him”. He fishes through the year in Goa’s rivers, ponds and canals with a simple line and hook, or smaller nets for shellfish, catching topro (zebra fish), gobro (rockfish), and bugdi (sardines), along with crab, catfish, khorsane (butterfly fish) and river prawns in the monsoon. He laments that Goans cannot live off farming and fisheries like they used to and are forced to depend on tourism for income.

Traditional fishermen are more judicious with how and when they fish, ensuring the biodiversity of our waterbodies. Freshwater crab and prawn fishermen fish at night, larger fish are caught with wide weave nets on boats, and smaller fish are snared with a line and hooks. Trawlers, in comparison, drag their nets along the seabed, destroying it and dredging and collecting fish indiscriminately. Worse, small indigenous fish or ‘weed fish’ are thrown back into the sea dead, regardless of breeding seasons or size.

Mud crab

| Photo Credit:

Simrit Malhi

Freshwater advantage

India’s 7,500 kilometre tropical coastline hosts a megadiversity of marine life; most of which are now severely depleted. Maharashtra, for example, registered its lowest marine catch in 45 years in 2020. This is no small statistic considering India is a big player in international seafood exports — ranking third worldwide.

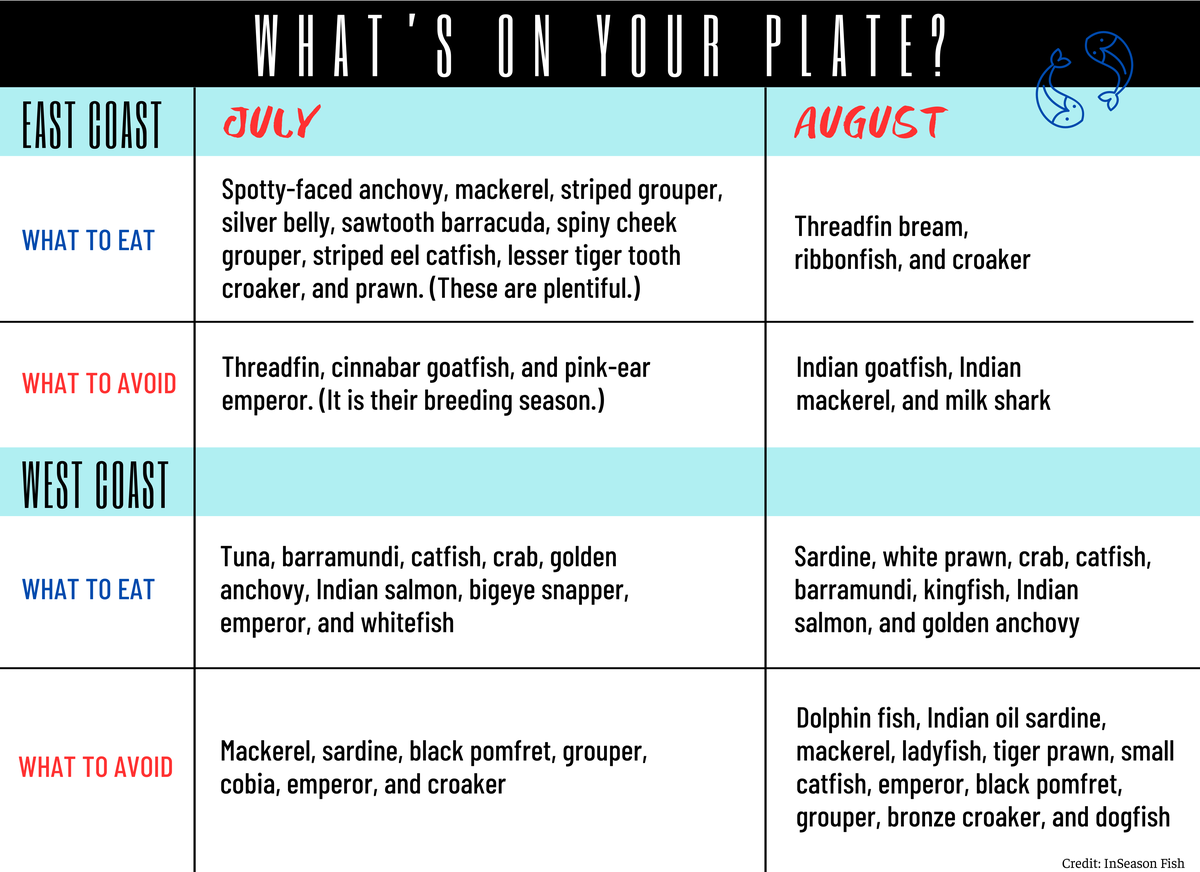

Every year, there is a ban on sea fishing (currently, it is along the west coast) during the monsoon, the main breeding months. The government-enforced ban adheres to traditional practices. While this means the smaller fish markets are shut and restaurants have to rely on frozen supplies, it’s also the best time to encourage people to look beyond their big fish staples such as tuna, king mackerel, and tiger prawns.

Traditional fishermen at an inland water body near Kodungallur in Thrissur

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

An assortment of monsoon fish, from clams and river prawns to chonak and bangda

| Photo Credit:

Simrit Malhi

The tradition of small-scale fishing is not unique to Goa; though fast disappearing, it is still practised in many coastal states such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Odisha and West Bengal with rich networks of backwaters, rivers and other waterbodies. While it’s mostly enjoyed by the local community, it would be beneficial to the environment, our health and pockets to take freshwater options and boat-caught small fish to a wider audience.

This market already exists in a small way in cities. In Kochi, Kerala, delivery services such as Fresh to Home and the relatively new city-based Happy Fish have freshwater options listed. “We have a large number of people who are knowledgeable about seasonality, and enjoy eating freshwater fish. And they don’t mind paying extra for it,” says Nidhin Mani, founder, Happy Fish. “We have tied up with small boat and hook-and-line fishermen from the suburbs and nearby villages to supply us with karimeen (pearl spot), kozhuva (anchovy), catla (Asian carp), paral (giant danio), mud crab, and the like.”

Local fish varieties such as poolan, branchi, thumbachi, pallathi, mullan, and karimeen caught by traditional boat fishermen kept for early morning auction at Kumbalanghi in Kochi

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

In the metros too, people are starting to explore smaller options. Mumbai-based nutritionist Neha Sahaya has stopped recommending sea fish to her clients because of the high amounts of mercury and microplastics found in them. “In fact, I don’t recommend local sea fish to any of my pregnant clients. Perhaps freshwater fish is a cleaner, more healthy option.”

“Of late, I’m noticing more youngsters interested in making healthy, seasonal choices. Since they don’t know much about fish, they often reach out to us on our official WhatsApp. We spend a lot of time daily sending them photos, and sharing how best they can cook freshwater and small fish.”Nidhin ManiHappy Fish, Kochi

Break food elitism

Food is political in India, and what you eat is an indication of your socio-economic status. Even our traditional vegetarian diet is rooted in privilege and caste hierarchies. That one can afford to eat fish such as king mackerel, Indian salmon, tuna and pomfret regularly is considered a sign of elitism, resulting in an excessive demand for these fish.

With the country’s economy booming, this also means that Indians now consume more fish than ever before — monthly consumption per household has shown a quantum leap in 10 years from 2.66 kg in 2011-12 to 4.99 kg in 2022-23 (according to the National Council of Applied Economic Research). Larger fish that were once only eaten on special occasions are now expected to be available throughout the year. And are, most often, chosen at the expense of smaller fish.

To add to this pressure, urban Indians, who are largely responsible for this leap in consumption, seem to lack generational knowledge about seasonal fish or their nutritional value. Food historian Vikram Doctor blames the supply chain and supermarkets for this change. “Supermarkets do not stock produce the way traditional markets do. Their emphasis is on standardised, easy to stock and carry products, which leads to standardised and simplified cooking,” he says. “Traditional markets have the possibility of stocking more seasonal, unique, unprocessed products that are challenging to cook, but also more rewarding.”

With most urban Indians purchasing fish at supermarkets and through delivery services such as Licious and Fresh to Home, there is a disconnect from local fish markets and fishermen.

A fisherman casts his net at Srinivasapuram beach in Chennai

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

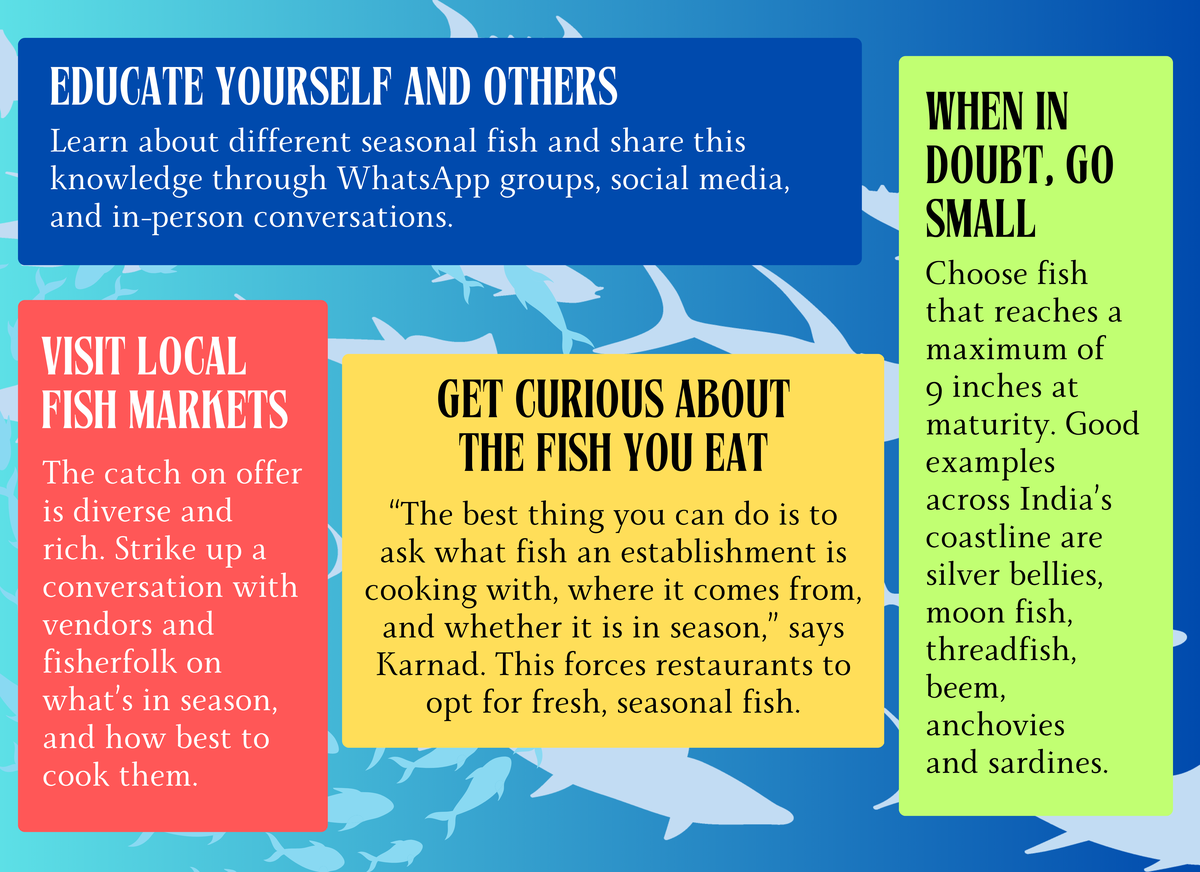

What you can do as a consumer

Today, fish in India is sold according to demand rather than supply. As researcher Divya Karnad learnt, what consumers eat has a strong impact on our coastline and plays a large role in the health of fisheries. Karnad is the founder of InSeason Fish, a five-year-old Chennai-based organisation committed to “promoting sustainable fishing practices and protecting the health of people and our oceans”. On the east coast, they work towards marine conservation by bringing together the main stakeholders in the fish industry: fishermen, stockists, vendors and the consumer. “We also collaborate with chefs and restaurants to promote sustainable seafood options on menus and provide tips for cooking that maximises flavour and sustainability,” she says, adding that they help educate consumers through fish market walks and children’s games.

On the west coast, Know Your Fish — started by a group of researchers in 2017 — focuses on influencing consumer trends towards healthier fish. They release a monthly calendar on social media illustrating which fish is safe to eat when, based on their annual data collection to test the vulnerability of each fish caught in the Arabian Sea. Several hotels, including Fort Tiracol in Goa, have approached them and now showcase their calendars at their in-house restaurants.

Though there is no empirical evidence yet to show if and how their efforts have made an actual difference, there are certainly more restaurants putting smaller fish options on their menus. In Kolkata, at Sienna Store & Cafe, head chef Koyel Roy Nandy insists on featuring smaller, lesser-known and even dried fish on the menu. “We are lucky here in Kolkata that there is a strong piscine culture. We have three local fish markets a kilometre from the restaurant, and we visit them and choose whatever is in season. The diversity of fish throughout the year makes for better nutrition.”

She tells me of the delicious kadamacha (mudfish) that comes from ponds and lakes that is a staple at Sienna, morula (anchovies) that are served beer-battered with chips, and dried hilsa that is used like bonito flakes. Though people still eat fish regularly in West Bengal, traditional knowledge of how they are eaten and how to choose them is getting lost. “We have a young kitchen and I make it a point to take them to the fish market so they can learn which fish to buy.”

Small fish are more nutritious. It has been reported that the vitamins and minerals in 1 kg of small indigenous fish (SIF) is equal to approximately 50 kg of big fish. A 2008 study on the consumption of small freshwater fish in West Bengal found that SIFs provide better nutrition since they are generally eaten whole — with the bones, organs, head and eyes, all of which contain important micronutrients that improve the immune system and aid growth and development.

4 ways to go small

In North Goa, New York-trained chef Sai Sabnis of Posa, a conscious restaurant, serves salt fish fritters in a recipe inspired from the Caribbean, in an attempt to modernise what eating small fish looks like. “In the more expensive restaurants, people don’t want to eat small fish because they don’t want to eat with their hands,” she says, adding that it also takes up more time for the kitchen to debone and process such fish. At Posa, she works around this by charging a higher value for these dishes — and customers are willing to pay. “Small, local fish are higher in quality than the large ‘big ticket’ fish like salmon and tuna because of the shorter supply chain.”

“Fish farming has its own problems. Potential over stocking can lead to heavy antibiotic use and the like. From a sustainability perspective, however, farmed fish like rohu and catla, which are lower on the food chain [they are not carnivorous], are relatively okay. They don’t require intensive inputs like, say, farmed shrimp do. Shrimp are carnivorous and have to be fed fish meal, which comes from destructive forms of fishing [bycatch from trawling is converted into this].”Divya KarnadInSeason Fish

A case for dried

One way to rediscover the knowledge of our piscine culinary heritage is to connect with the communities that have engaged with it over generations. The Kolis, Mumbai’s indigenous fishing community, are an ideal example.

They consume a wide variety of fish, including smaller pelagic fish such as lepo (sole) as well as vam (eel), shrimp, a variety of molluscs, and even a few amphibians like nivte (mudskipper). And a large part of their diet in the monsoon consists of fish that is dried during the preceding summer months, another tradition seen throughout the country.

A woman hangs bombil fish to dry in the sun at Madh fishing village in Mumbai

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The history of dried fish started in the medieval era. In the mid-19th century, dried fish got to India via the port cities of Mumbai, Visakhapatnam and Chennai, and was distributed around the country via interstate and intrastate trade railways. Popularly known as shutki, it is emblematic of the cultural oneness of India’s coastline. From the famous ‘Bombay Duck’ or bombil to the dry fish markets on the border of Bangladesh that service Northeast India and West Bengal, there is still a thriving industry across the country. It’s urban India that’s disconnected from it.

In Goa, Doctor reminds me of the importance of the Purumentachem Festival. This annual ‘Feast of Provisions’ kicks off just before the rains start, in May. Old women from around Goa set up stalls with pickles, fermented foods, vinegar and dried fish. The stalls of dried fish are among the most sought after. “It was, and is still, common in the rural areas for monsoon meals to be made up of only rice, dal and dried fish,” he says. “The strong flavour and high nutritional value removes the need for much else.”

Cooking river fish in hay the traditional Goan way, wrapped in banana leaves

However, very few practise the tradition of salt-drying fish in the sun nowadays because the smell is so pungent. “This was traditionally done in large outdoor kitchens that people don’t have access to any more. Even hotels that might have access to space, are warned by management to stay away from these practices.”

Our taste buds have been colonised into a western ideal of a more ‘sanitised’ palate. A change could spell good things for our health, culinary practices, and waterbodies.

The writer is a permaculture farmer who believes eating right can save the planet.

#Small #fry #focus #good #time #learn #seasonal #fish